Walk into any skinhead gig, leaf through a photocopied zine, or scroll through certain corners of punk Instagram, and you might stumble upon an arresting image: a skinhead, arms outstretched, nailed or strapped to a cross. Sometimes bloody, sometimes cartoonish, often political. It’s called Skinhead Crucifixion — a provocative visual loaded with history, defiance, and contradictions. But where did it come from? Why a crucifixion? And what does it say about the skinhead identity?

Martyrdom meets working class reality

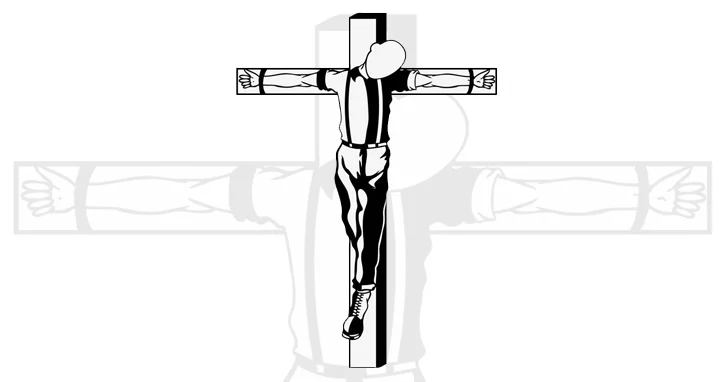

The image is unmistakable. A cropped head, boots laced tight, braces pulled taut, and arms wide open — pinned, strapped, or wired to a wooden cross. Often flanked by cops, bootboys, or businessmen. Sometimes there’s a boot in the face. Sometimes there’s a headline about youth crime or fascism underneath.

At first glance, it might seem like shock art. But look closer and you’ll find a loaded symbol of class warfare, scapegoating, and media persecution. Skinhead crucifixion borrows heavily from traditional Christian iconography, particularly the suffering Christ. But instead of a holy man, it’s a skinhead. Instead of divine forgiveness, it’s a public trial by media and society. It’s martyrdom – but with braces and cherry-red boots.

It’s martyrdom – but with braces and cherry-red boots.

Origins

There’s no single origin point, no one artist to pin it on. But traces of the skinhead crucifixion image started popping up in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s – around the time the second wave of skinheads collided with Oi!, anarcho-punk, and a Thatcherite Britain gone sour.

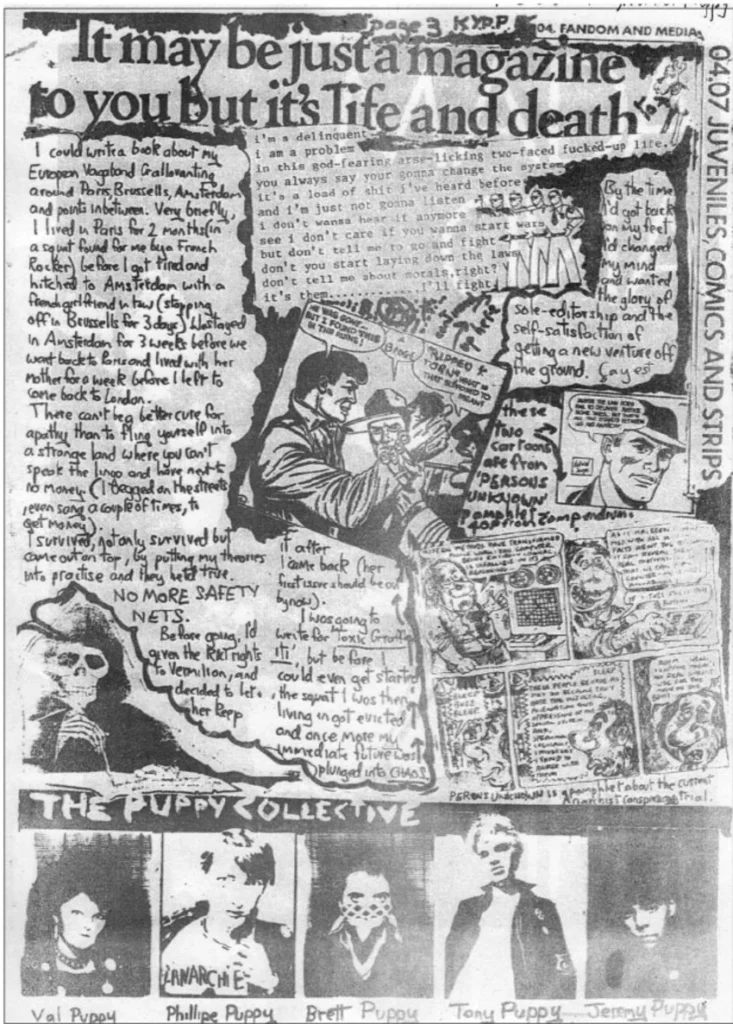

© Derek Ridgers

In zines like Kill Your Pet Puppy, and later in more radical skinhead and SHARP-affiliated publications, the image served as a stark visual metaphor. It reflected how skinheads — once just working-class youth with cropped hair and a love for ska — had become demonised. The media painted them as booted thugs. Middle-class punks distanced themselves. Politicians scapegoated them for social decay. The crucifixion image said: They’re killing us. Not literally — but culturally, socially, spiritually.

© Researchgate / Matthew Worley

And for some, it was also a mirror: a critique of the skinhead movement itself, tearing itself apart from the inside – divided by politics, violence, and ego.

The media villain

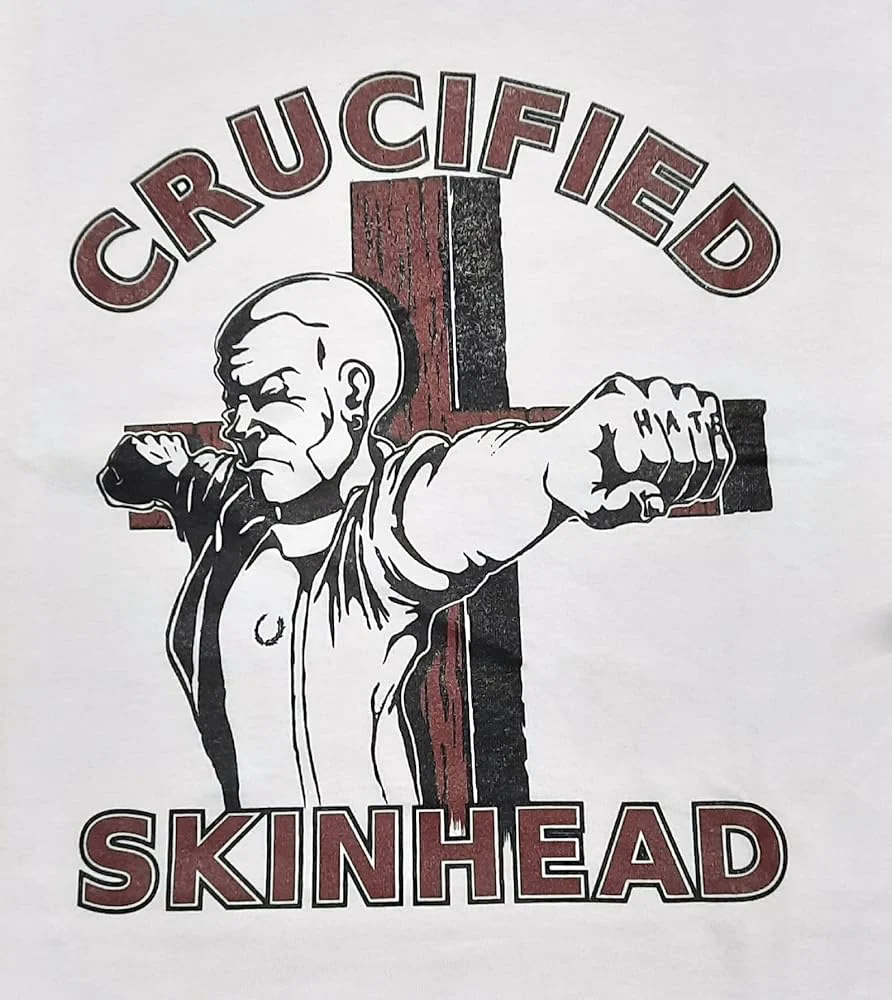

If you were a skinhead in the 1980s, chances are you were painted with one brush: dangerous, racist, violent. It didn’t matter if you were red, white, or SHARP – the tabloids had made up their minds. The crucifixion became a symbol of that persecution. It was plastered on posters, tattooed on backs, and graffitied on squats. It was a response to every lazy headline and every middle-class sneer. It shouted: Look what you’ve done to us.

The irony? Many of the people behind the image weren’t religious. Some were atheists. Others were anarchists. But they understood the power of Christian martyrdom — how the crucifixion could speak to unjust punishment, to being nailed down without a trial. That’s what the image became: a raw scream about being misunderstood and thrown to the wolves.

Multiple meanings

Depending on who you ask, the skinhead crucifixion is either a powerful indictment of society’s hypocrisy, or an embarrassing bit of self-pity. Some see it as righteous. A powerful image of class warfare and state violence. A working-class kid, left to rot, because he doesn’t fit the mold.

Others roll their eyes. They see it as melodramatic. Skinheads as victims? Give us a break. Plenty of skinheads gave as good as they got, and some were happy to throw the first punch. But maybe that’s the point. The crucifixion doesn’t pretend skinheads are saints. It just says they’ve been crucified — by misunderstanding, by media, by class prejudice. Whether they deserved it or not… well, that’s up for debate.

An icon today

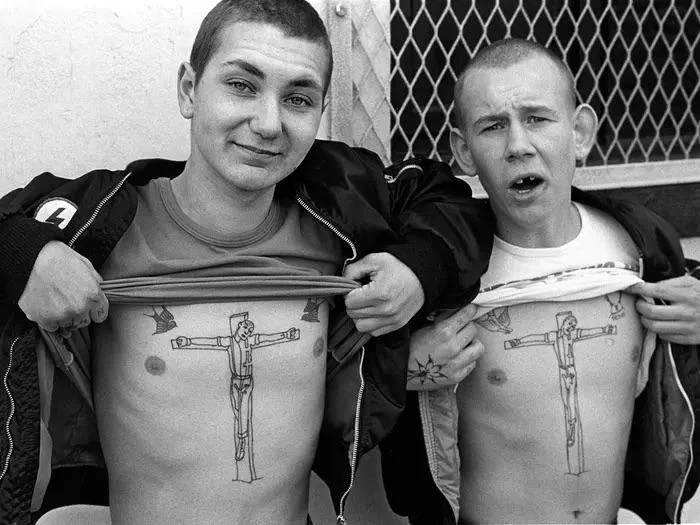

Today, the image lives on in patches, tattoos, album covers, and street art. It’s been reimagined in anti-racist SHARP styles, in RASH aesthetics, and even in tongue-in-cheek memes. It’s gone digital — but the core idea remains.

When a scene is vilified, when your identity becomes shorthand for something ugly, there’s power in reclaiming the narrative. In saying: You think we’re evil? Fine. But look what you’ve done to us. For some, it’s about honouring those who’ve been misunderstood. For others, it’s about owning the villain role and flipping it on its head. Skinhead crucifixion isn’t about Jesus. It’s about judgement. About how a youth subculture born from reggae, soul, and working-class pride got turned into a moral panic — and nailed to a cross of headlines, hypocrisy, and hysteria.

You think we’re evil? Fine. But look what you’ve done to us.

You can mock it. You can wear it. You can tattoo it on your chest. But you can’t deny its punch. In the end, it’s more than art. It’s a scar. A reminder. A protest frozen in an image. And like the skinhead scene itself — it’s raw, misunderstood, and refuses to die quietly.